It’s 2 pm in the afternoon, between classes, and most of us are forking the previous night’s leftovers into our mouths while we wait for the last stragglers to arrive. We are sitting around two tables haphazardly pulled together in a dim, dusty room filled with odd bits of furniture. Some magazines and books line one wall. Together we form the team behind Antithesis Journal, an arts and communications publication run by graduate students. It’s not much, but we call this the Antithesis room, unofficially our very own meeting room on campus at the University of Melbourne.

The editor-in-chief calls the meeting to order, and we start with a quick recap of who isn’t able to make it today. (Getting everyone in the same room at the same time is the eternal curse of a student publication.) We begin by hashing out a date for the upcoming launch of this year’s issue, and the rest of the lengthy meeting is filled with production updates and other minor controversies. The dull score of clicking keys punctuates the discussion as we tap notes into our laptops and send surreptitious comments to one another via Facebook messenger.

Recent iterations of the journal are generously sized, with ample white space and full-page illustrations on the cover and throughout. The design, marketing and editorial work has been produced by graduate students at the University of Melbourne, with the content and artwork supplied by independent contributors from Australia and across the globe. Laptops—many branded with the sleek Apple logo so coveted by young creatives—are the connecting threads that act as the basis of the production process; Submittable, Google Drive, InDesign, and social networking sites are the main media through which Antithesis begins to take its shape.

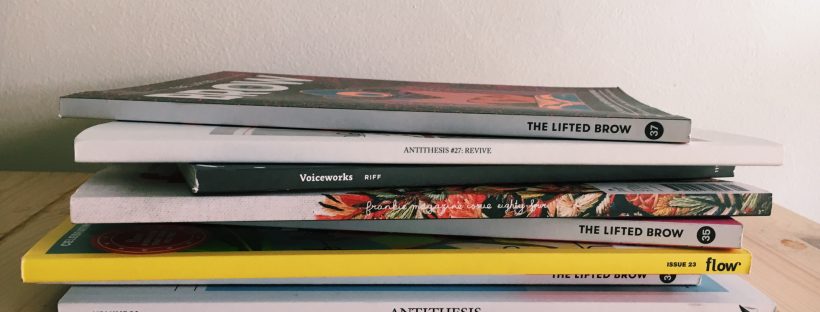

For the new digital natives, the printed form has become an object of value in an ephemeral, content-saturated online media environment. In the increasingly click-bait-driven 24-hour media cycle, the niche print magazine has become a carefully curated, collectible artefact that offers its readers a tactile reading experience that cannot be recreated digitally. These small-circulation publications are rejuvenating print culture with creativity, invention and—paradoxically—the power of digital technology.

Since the rise of Web 2.0, mass market magazines have suffered as readers and advertisers flocked to digital media for accessible, convenient and free content. In response, large magazine publishers pursued their readers into the digital realm, becoming multichannel media ‘brands’ with online offerings ranging from social media, video, websites, events, and more. The ‘death of print’ was pessimistically bandied through the media. Lifestyle magazines such as Cleo and Zoo struggled to stay viable and relevant in a new cultural momentum towards diversity. As these magazine giants folded, independently created magazines (such as The Gourmand, Kinfolk, Apartmento, The Lifted Brow) were quickly filling the gap.

The advent of desktop publishing in the 1980s and the rise of the internet since the 90s has allowed for a do-it-yourself publishing culture that enables quality design, global digital distribution and community-building through websites and social media platforms. The barriers to entry have lowered, and indie publishers can use digital technologies to put together, publicise and distribute their publications.

Indie magazines and journals cover an endless number of special-interest topics, such as Nordic knitting (Laine), food and drink (Gather), cycling (Boneshaker), body modification culture (Sang Bleu), travel (Cereal), interior design (Apartmento), craft and culture (Frankie), and many more.

‘Because of their small circulation,’ says Megan Le Masurier from the University of Sydney, ‘the indies are not unlike zines, where ‘embodied community’ develops around these material media objects imprinted with care and creativity’.

Yet independents face their own challenges: raising funds for production and printing and the challenges of free labour. Some magazines are funded by grants or organisations (such as Antithesis), others by Kickstarter or higher cover prices, but as with other areas of Australian arts culture, much of the labour spent producing these magazines is underpaid or not paid at all. But this is a labour of love, as the collaborators from niche communities willingly share their passions and united vision in the print-making process.

Millennial consumers are wising up. We are becoming savvy about consumer culture, and we are now doing and making things on our own terms. In the 1980s, Alvin Toffler coined the term ‘prosumer’, which is the blurring of roles between consumption and production. For Tofflin, this marks a ‘shift from a passive consumer society to one in which many people will prefer to provide home-grown services to themselves and others, selectively producing and consuming depending on their interests and expertise’.

We see this played out in contemporary consumer culture as millennials tire of the high-waste, use-and-discard culture of previous generations. We desire publications that are beautiful and sustainable with topics that interest us, critical writing that engages our social compass, and most of all a tribe to feel connected to.

This rise of the prosumer is a move towards a selective, crowd-produced consumption that forms a niche, loyal audience through word-of-mouth and grassroots marketing. It is a movement away from mass media and towards a more democratic, personal, selective consumption produced through networked online communities.

Another example here at the university of Melbourne is Publish or Perish, a small magazine-like publication put together by members of the Publishing Students’ Society. Started earlier this year, Publish or Perish is a compilation of edited short fiction pieces submitted by contributors through the submissions software called Submittable.

We are both the creators and the market for this publication. Our common interest: the writing and publishing of words. The team behind Publish or Perish, and their family and friends, are likely the main purchasers of this publication, as well as those few who are interested in running it for next year; yet, somehow, this does not diminish the pleasure of producing it. We are building something for ourselves, something that we can hold up and say: ‘I did this, and this and this.’

A small room of students may not look much like a publishing revolution, but it’s a revolution of the millennial kind—a savvy, independent, creative shift in publishing that combines the possibilities of print and digital media to connect subcultures and their stories across the globe.

_____________________________________________________________________________

If you would like to be involved in publishing at the University of Melbourne, you can find out more at University of Melbourne Publishing Students’ Society and Antithesis Journal.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Clarissa is studying her Master of Publishing and Communications at the University of Melbourne and is an editor at Grattan Street Press. When she does not have her head in a book, she spends her time signing up for impromptu hobbies and pondering the future of the publishing industry.

Image supplied by author.

Leave a Reply